Escape from Facebook~ 15 min

Between 2009 and 2011, a countless number of opinion articles attributed responsibilities for the uprisings that hit part of the Middle East and Latin America to the power of social networks like Facebook and Twitter. The tone of said articles mixed technological and civilizational triumphalism: “See how our superior values are finally getting through to these uncouth and unwashed peoples, thanks to to the technological wonders of the Internet.”

As these scribes saw it, these social networks had allowed the coordination of a technically apt new generation that demanded freedom and democracy from oppressive regimes. Let’s leave aside for now that later and more serious analysis about such phenomenons have revealed that the usage of social networks for protesting was greatly exaggerated. Or that the true story is of how there are a huge number of journalists who have no physical presence on the locations they are supposedly covering, don’t speak the local language and don’t know the local history and are simply heading to Twitter and Facebook to steal a few photos and videos and concoct some tall tale about what is supposedly going on.

Let’s instead ask the question – what’s the true potential of social networks like Facebook for radical politics?

In Portugal, during the period of anti-austerity protests that started in 2011, it was possible to witness the astounding speed with which Facebook events for demonstrations like Screw the Troika and the Sieges of Parliament grew, with thousands of people joining in by the hour. Irrespectively of such numbers not translating necessarily into street participation, it was a strong signal that political participation was escaping the circle into which it usually delimits itself and reaching a wider audience. As members of Guilhotina, it was in part our witnessing of Facebook’s power to reach people that lead us to invest in the platform.

Several of the people that would eventually form our collective were already administrators on a variety of Facebook pages. Growing audiences pre-2014 was a vastly inferior challenge to what it is today. The time and content investment that would previously generate thousands of “likes” is now lucky if it generate a few hundreds, while reaching a much smaller number of people.

Taking into account that Guilhotina was launched in late 2013, this change in dynamics circa 2014 was particularly obvious to us in the way the growth slowed, despite the fact that our collective work was much more prolific.

What happened in 2014?

Before 2012, a post equaled a visualization, as long as someone had pressed “Like” on a page. Facebook then introduced its “organic reach”, which restricted the amount of people who initially see a post to around 16% of the page’s total audience. Depending on the amount of interactions that the publication gathers (comments, shares and likes), the Facebook algorithm will decide whether to show it to more people or not. In 2014, the organic reach percentage fell further to 6,5%.

If 16% already was a challenge, 6,5% seems to have been not only a quantitative but also qualitative jump in difficulty towards reaching the audience. The organic reach has continually fallen since then and is now between 1 and 2%, depending on a number of factors; for example, smaller pages who are just starting out get a higher organic reach, which falls as they grow. The first 2.000 likes are notoriously easier to reach than those who come after. This is probably a strategy to not discourage those who are just now investing in the platform and make them feel that, in reaching a certain milestone, you might as well continue, despite the reduced returns.

Facebook justified the implementation of organic reach with the necessity of increasing the selectivity of what made it to users’ feeds, as content became ever more abundant. Of course, if a genuine concern for users existed, Facebook could simply offer them more tools to curate content, instead of taking away users’ power and giving it over to the algorithm. In reality, these alterations obviously served to reinforce to advertisers the necessity of paying Mark’s tithe in order to be allowed to reach their audience – or, more accurately, their consumers.

For political pages, be they linked to movements, information collectives or others – who can’t count on millions in financial resources to “promote” themselves – this was obviously a step towards irrelevance, whilst capital saw its hegemony reinforced, despite now having to pay the Zuckerberg tax.

Is Facebook betraying its free communication principles?

Not at all. Only a tech journalist, his brain addled by overexposure to inspirational Steve Jobs quotes, could entertain such a notion. Facebook’s end goal was always extortion via monopoly, like any self-respecting tech startup.

First step: identifying a new and unexplored market, recently made possible by the dissemination of new technologies. Second step: gather investment capital and go in full steam ahead to dominate the new space (in this case, expanding the number of social network users), even if it costs you money. Which in Facebook’s case happened until 2009; it lost money for 4 years and a half.

Such losses are expected, for this is the moment when the monopoly to come is seeded. If there was a concern for immediate profitability, growth would be much slower. And who could say what might happen then? What if an already established giant like Apple, Microsoft or Google said “Nice idea, I think I’ll steal it”?

No, one needs to guarantee that when the moment of truth comes, product usage is so widespread that users can’t even consider an alternative and that there won’t be space for competition to grow. Not joining Facebook? But how, now that all your friends and family only communicate through it, now that all events are filtered through it? Do you want to be ostracized? Join in, it’s free and always will be. Ok, you’ve joined and found out that it’s wearying, what now? Leave Facebook? Everyone you know is there. All your interests, all your photos, all your conversations. Unthinkable, social suicide.

It’s at this point, when life without Facebook becomes unimaginable, when it’s already on course to hit the present number of 2.234 million users (January 2018) and capture a majority of the social networking market – despite having fallen from a peak of almost 90% to the current 65% (April 2018) – it’s at this point that the walls arise.

Now comes the third step: exercising monopoly power. Like Google with search engine advertising (91% of market share in April 2018) and Microsoft with operating systems (81% of the PC desktop market in April 2018), Facebook reigns uncontested in the field of social networks, which means it dictates prices and terms. Thus its fabulous wealth, due to advertisers’ competition to reach the juicy consumers inside the social network. Facebook possesses the advantage, possibly even more than Google, of being a platform where users themselves do the work of self-segmenting through all the intimate information they share with Mark, thinking they share themselves with friends and family. In terms of marketing, to be able to know your targets with such clarity and choose them with such precision is a priceless gift.

This passage from the second step – expansion – to the third – monopoly – thus becomes the high water mark for the political possibilities of Facebook, trapped between the moment when it needs everyone aboard – and thus places fewer restrictions to communication – and the moment when it hits the necessary audience to start squeezing those who post on the platform, whether their content is commercial or not.

Consequently, Facebook is today an enormous shopping mall. A place where people gather, talk, date, have fun, but in which the whole social component is nothing more than bait for the true purpose of dragging everyone inside a franchise and get them consuming. Brands pay Facebook rent for the right to have a space in Mark Zuckerberg’s all-powerful worldwide shopping mall.

And like a mall, it wasn’t created with free political debate in mind. Behind the shiny facade, the long cement corridors hide, leading to surveillance rooms where security can track our every movement through a thousand eyes in the ceiling; where marketers take note of every look, every step, every purchase; where accounting departments calculate how many cents each of our dollars is worth.

Of course, like in any other mall, visitors can gather peacefully at the local Starbucks’ comfy sofas to discuss the advantages and disadvantages of the dictatorship of the proletariat. But just try to become too noisy, start distributing pamphlets, organizing, and soon four security guards and two policemen will show up, asking what’s the big idea and to please get lost because capital has more important things to worry about.

The ideal environment envisioned by Facebook is thus one of aggressive normality and centrism, where neither consumers might feel bothered nor advertisers worry that their contents will appear next to corpses in Syria and Palestine.

The way Facebook constructs such an environment, beyond enforcing the already mentioned tax to reach your audience, is through opaque mechanisms of censorship.

Methods of censorship

The first of these is the pseudo-democracy of reporting, under the logic that if a sufficient number of people feel that something is offensive, it probably is. The abuses that such a system make possible are easy to predict, and it’s frequent for both the extreme left and right to see their pages taken down as part of reporting wars.

But if 10 or 10.000 racists report and take down a page for black rights or if 10 or 10.000 misogynists do the same to a feminist page doesn’t make the process any more or less democratic, especially since the final decision to remove content is left up to Facebook’s censors. The reporting process just gives Facebook justification to get rid of everything that looks like it might scare consumers and advertisers. And whenever a page is taken down permanently, you have to rebuild from almost zero, ensuring you’ll never leave the ghetto of a small audience.

At the same time, one doesn’t require prescience to know that, even if we gathered 1 million users to report Raytheon for manufacturing weapons used to kill innocent civilians, we would all die of old age before their page got taken down.

Guilhotina only suffered this type of censorship once, when we published the pictures of the 2017 “Queima das Fitas” (a graduation ceremony for college graduates) rapists [a group of students aboard a bus who recorded and cheered while an unconscious girl had her genitals groped by one of their number]. But we also know of the experience of a bigger page – which shall remain nameless, as it was since sold off and turned into a garbage bag – which was recurrently taken down, especially when posting about Turkey, a country with a particularly well developed troll sector.

A sinister aside: after one of these attacks, all the administrators and ex-administrators of the page were locked out of their personal accounts under the pretense of having uncommon and possibly fake names (which was far from the fact) while at the same time demanding they send official IDs to have their accounts unlocked.

After the censorship of the report comes the censorship of Facebook’s vague community standards. These are the universal tool used to give a moral cover to censorship, since the contents are eliminated under the pretense of protecting users from some kind of trauma, such as the that caused by seeing female nipples. Obviously there are genuinely censurable contents, published by sick minds, but the effect of these rules in left politics is to prevent bringing to the light of day the real world consequences of concepts such as racism, imperialism and misogyny.

Have you recorded a police killing of an unarmed black person? Or children torn apart by bombs in the Middle East? Or women being stoned in Saudi Arabia? Sorry, but publishing such violence violates the community standards, you’re all banned. But only if you’re a small time journalist, activist or accidental witness. If you’re the New York Times, Washington Post, CNN or BBC, no atrocity is off the menu, no matter how graphic, as long as it helps launch more military interventions.

This process of delegitimizing everything which is contrary to the interests of capital is only accelerating as all the stupidity around fake news – summoned by Trump but then given new force by the higher echelons of the american Democratic party to justify Hillary Clinton’s pathetic defeat – has triggered a russophobic wave in the West that is being used to enforce greater controls on information. Google took the initiative with the delisting and deranking of a number of independent sites, especially those with anti-imperialist postures and ceptical of official narratives that blame Putin everytime someone spills coffee in Washington.

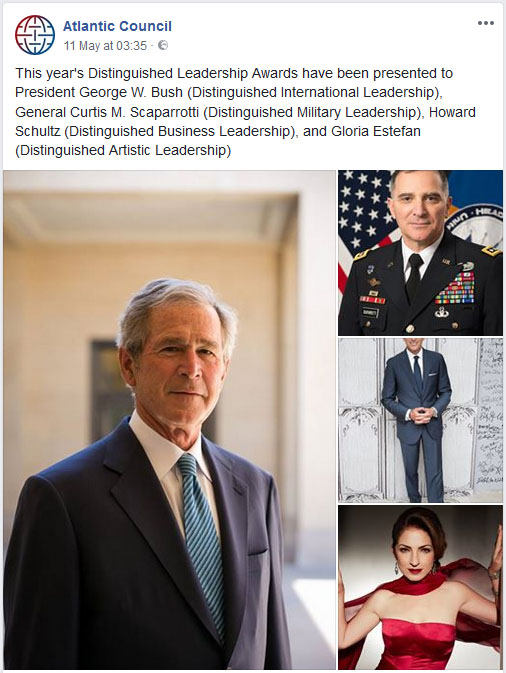

Now it’s Facebook’s turn in establishing its own system of more overt censorship, having announced a partnership with the Atlantic Council to decide what is or isn’t real news.

Let us not forget that the Atlantic Council is a think tank financed by know champions of democracy, peace and freedom such as: United Arab Emirates, National Oil Company of Abu Dhabi, Airbus, Carnegie Corporation, Chevron, UK Foreign Office, NATO, Blackstone Group, Google, HSBC, Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, US State Department, ExxonMobil, JPMorgan Chase, Oil Corporation of Turkey, Pfizer, Bank of America, Boeing, BP, Deloitte, Bank of Investment of America, Northrop Grumman, Shell, Statoil, four of the five branches of the US armed forces (Air Force, Army, Marines and Navy), Wal-Mart and the Defense Ministries of Norway, Sweden, Japan, Latvia and Lithuania. This is but a small selection from amongst many, many other great names of humanism and civilizational progress.

Not that peculiar things related to the interests of imperialism haven’t already happened. At Guilhotina we denounced the quiet disappearance of our post about the White Helmets, which we only noticed by accident when we tried to find it to leave as reference in a different post. During the one year and four months since it was originally posted, we never received any notification that the content had been removed. We are left with the suspicion that the reason why Facebook’s chronological search tools have been getting worse is due to their intentions to start editing the past in such a manner. Our White Helmets post was briefly restored after we first found out of its disappearance, but it has meanwhile vanished once more.

Or what about that one time when Facebook insisted that “an error occurred” when we tried to post about the then ongoing turkish invasion of Afrin, but allowed posting about everything else. We tested posting the images of the turkish offensive with a different text which didn’t mention Turkey, Erdogan, kurds, Afrinc, etc. and behold, no more “error”. It was also around this time that many pages linked to the kurdish cause were purged from the social network. The media moment of the kurds as heroes and heroines fighting ISIS was gone, replaced by the necessities of realpolitik and allowing one of NATO’s most important members to quietly commit a bit of ethnic cleansing.

Alas, capital simply can’t allow a propaganda machine of Facebook’s scale to freely run around under libertarian principles. It’s to be expected that the social network would eventually have to play a more overt political role.

And what does all of this mean to us, in trying to answer the question posed at the beginning of this text? The truth is that we can’t abandon Facebook completely, at least for now. There are unfortunately too many people trapped in there for us to simply turn our backs to the platform. But it is certainly true that the false promise of reaching new audiences that it made in the past is practically dead and buried. At this point in time, investing in Facebook as a platform is an error. Facebook, for those who don’t pay the Zuckerberg tax, is nothing more than a notification system for an audience that already knows us, and even they see us less and less. Notification: we published a new article. Notification: such and such event is going to happen. Notification: a new Mapa newspaper is out.

It’s only going to get worse from here on out. It is thus imperative that all political collectives that want to have a long-term voice create their own online platforms as soon as possible, invest in multiple social networks and think of new ways to reach their audiences in the real world, while using Facebook in an utilitarian manner. Because one of these days, someone will press a button that says we are all fake news and that will be the end of that on Mark’s shopping mall.