Portugal // “In the good old days”~ 7 min

Por Guilhotina.info

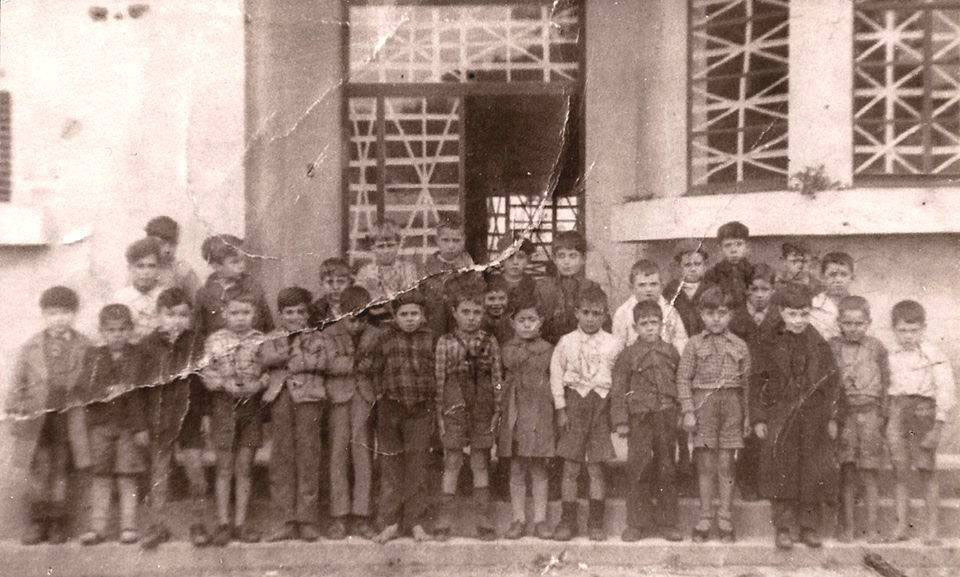

The past is never truly dead and buried. It must be contested or we risk losing historical truth to the fabrications of the resentful and opportunistic. This is true as well regarding the reality of Salazar’s dictatorship. Right-wing trolls diligently work towards inundating social networks with falsifications. They seek to obscure the truth about the life of bare feet and empty stomachs that most Portuguese experienced if they were unlucky enough to be born during that period.

That is the reason why, for some time now, we follow the work of the page “Antigamente é que era bom”. The page’s name is a common expression somewhat similar in meaning to “in the good old days”. The page seeks to restore historical truth in a simple and graphic manner by using photos and documents from the dictatorship’s period. We interviewed the author to find out what motivated the project and what he has learned about those who long for another Salazar.

What made you start the page? What is your relationship with “the good old days”? What are the page’s objectives?

What made me start the page was seeing completely absurd commentaries in the comment sections of online newspapers. Furthermore, I was already in possession of documents (which I still have) from PIDE/DGS [the dictatorship’s secret police] that were sent to the local council of the locality where I was born and which ended up in my hands. I started sharing them on my personal page. Almost all of them were about PIDE’s persecution of emmigrants who wanted to leave for France (something the “good old days” types deny ever happened).

After verifying that people were interested and receiving a few incentives from friends, I decided to start a page. I have no other objectives beyond unmasking the myths and arguments of those who long for Salazar. I was born in 1960, I still lived some of the “good old days”. I’m the son of someone who always opposed the Salazar regime. I’m not affiliated with any political party, I’m a defender of democracy and the Constitution of the Portuguese Republic. I hold office in my local council, but I don’t live off politics, I have a profession related to education. I like politics and try hard to make sure that people can live freely in democracy. I’m not on the payroll of any political force, contrary to what the fans of Salazarism accuse me of.

I also wish for young people to know what those times were, but I think they are also the ones most vulnerable to manipulation by the people who long for Salazar.

Who are the different types of people who long for the past and what are their profiles? Is there any noticeable patterns among them? For example, class, sex, geography, etc.?

I don’t know… I think they are spread all over the country and many are emmigrants. I think some are young people who attack democracy because they had to emigrate, or for having some problem in their lives, namely having difficulty in finding a job.

There are also those who are pure Salazarists and those resentful with what happened after the 25th of April [the Carnation Revolution]. They never accepted democracy. And we also get the “returnees” [the colonists expelled from the colonies and forcefully returned to Portugal after the revolution] and former combatants in the colonial war.

I think they are mostly concentrated in Lisbon and the north of the country. Some are fake profiles made by people who use them to undermine democracy and lead young people to believe that things were much better “in the good old days”, that there was no unemployment, that everyone lived well, etc. Others were poor people (very poor) during the Salazar regime and they’ve convinced themselves that they are now rich. That is one of the arguments that I like to use to shut up the people longing for the past. They certainly seem to find themselves lacking in arguments afterwards.

What are most common myths and arguments invoked by those longing for the “good old days”?

The myths are that people lived well, that the people who lived badly brought it upon themselves, that PIDE didn’t hurt anyone (or only hurt people who didn’t want to work, meaning the communists), that they didn’t persecute emmigrants, that if children went barefoot it was because they wanted to or because they were gypsies.

They also argue that today is unlike the “good old days”, that everything is wrong, that politicians steal everything and that nobody stole anything before, there was no crime, pedophiles or corruption.

They also argue that those who refused to serve in the colonial war are traitors to the Homeland, that they sold off Portugal, that Soares [prime-minister and president of the Republic for the Socialist Party after the Carnation Revolution] was a criminal, etc. etc. Curiously, they insult Soares more than Cunhal [historical leader of the Portuguese Communist Party].

How do they respond when confronted with evidence of what reality was like in the “good old days”?

They keep at it and don’t care about evidence. They have an excuse for everything. There isn’t a single piece of evidence they will agree with. For example: if it is proven that children wore shoes in wartime countries during the 40s of the XXth century, they will say and insist that children went barefoot in all countries, just like they did in Portugal. Despite the evidence (for example, photos featuring north-american soldiers in France next to children wearing shoes) they still insist that most children went barefoot in all countries.

Have there been changes in the people longing for Salazar since the page opened? For example, in the type arguments used, in the regularity or persistence of those longing for the past, etc. If so, which?

I think those have all remained the same since the page started. But the more evidence one publishes, the more they insist in denying it.

What sources do you use for the documents and photographic evidence from the “good old days”? Are there any that stand out?

As I said before, I have a few documents about the persecution of emmigrants in my locality. Other documents and photos I find on the Internet (which has many, fortunately) and some are from people who send them to me for publishing.

What are today’s similarities with the “good old days” in the political scene? Are there notions and discourses being salvaged or that never disappeared completely, for example? If so, what factors do you think justify such a resurgence?

There is no similarity. Today we have freedom (since the 25th of April). Today, those who long for the past criticize the government and hurl every insult at politicians, they insinuate false facts and nothing happens to them. If these were the “good old days” they wouldn’t be able to. Of course, not everything is good and there are reasons to criticize what’s wrong. But to compare those days of pure misery with today is like comparing night and day. Obviously, the populist and right-wing discourse worries me and we need to combat it. But I also know that Portugal still has many defenders of the regime born out of the 25th of April.